For daily commuting and most short errands I pedal a bicycle: no fossil fuels used there, and no more carbon emissions than if I were merely exercising for health and enjoyment.

For most longer trips (and some short ones) I drive, and I’ve kept track of the odometer readings and approximate fuel economy of all 2.5 of the cars I’ve ever owned. But I usually don’t drive alone, and I’ve never kept records of exactly how often I do, so it would be tricky to figure out my personal share of the associated gasoline and CO2. I’ll try to make an estimate anyway, but not today.

I’ve occasionally ridden on buses and trains, but not often enough for either to have made a significant contribution to my energy/carbon footprint.

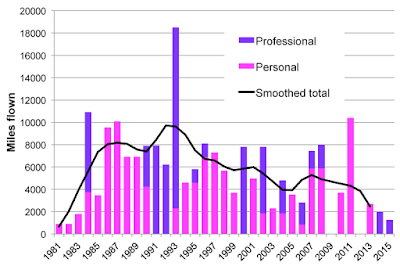

That leaves air travel, which in many ways is the most interesting. It didn’t take me long to go through old credit card statements and other records, to reconstruct a list of every trip I’ve ever taken by plane. With just a bit of guess-work I count 71 trips over 35 years. Here’s a plot of my air travel history:

I never flew at all as a child; my first four flights were trips home from college (to St. Louis from Minnesota). Then in 1984 I flew to visit graduate schools on both coasts, and chose to attend one in California. That choice left me making regular flights back east to visit family and friends over the next seven years (including one year in my first full-time job). In 1991, after three flights for job interviews, I moved to Iowa—within driving distance of my immediate family but now a long flight from professional collaborators back in California. In 1993 there were more job interviews, plus my longest trip ever, to a conference in Hawaii. But I ended up in Utah, from which I’ve regularly flown to visit family and to attend professional conferences and workshops. Recently, since my dad’s final illness in 2011, my personal air travel has declined.

The mileages in the chart are somewhat uncertain because I don’t remember the locations of all the intermediate stops and transfers. But by my best estimate I’ve flown a little under 200,000 miles, in a little over 200 separate up-and-down flight legs. Over the last ten years I’ve averaged 3800 miles per year, and my lifetime average (since birth) is about the same. But as you can see from the chart, I was averaging twice that amount during grad school and for several years afterwards.

So is 3800 miles/year a lot or a little? The answer is both, depending on the standard of comparison:

- The total number of passenger-miles for all U.S. domestic flights is about 600 billion per year. If we divide that by the U.S. population (320 million), we get an average of about 1900 miles/year per person. So my 3800 miles/year is about twice the national average. (If you include international flights, then the average American probably flies somewhat more than 1900 miles/year—but nowhere near twice as much.)

- World-wide, annual air traffic comes to about 4 trillion passenger-miles, or about 550 miles per person. So my 3800 miles/year is nearly seven times the world average.

- Among my friends, on the other hand, 3800 miles/year seems to be on the low side. Most of my friends are well-educated, upper-middle-class professionals who, like me, travel for professional reasons and to visit families and friends scattered across the U.S. Unlike me, however, most of them also travel overseas occasionally. And many of them just seem to fly more often than I do. My guess is that most of my friends fly about twice as much as I do today, or about as much as I did 20-30 years ago. A few of them fly significantly more than that. One of my acquaintances has accumulated nearly two million frequent-flyer miles on a single airline.

Based on these numbers, I calculate that for my typical mode of flying (coach class on a narrow-body jet with an average flight leg of 950 miles), the average emission rate is 0.415 pounds of CO2 per mile. Multiplying by 3800 miles/year, I find that my flying contributes 1600 pounds of CO2 to the atmosphere in an average year. (It was much higher 20-30 years ago, when I was flying twice as much and planes were less efficient—mostly because they tended to be less full.)

As always with such estimates, this result is rather fuzzy because of all the approximations and assumptions that went into it. Even if all of my calculations are perfectly “accurate,” I haven’t included the emissions associated with manufacturing the aircraft, or operating the airports, or ground transportation. Also, aircraft have other climate impacts besides CO2 emissions, and I’ve applied no enhancement factor to account for these effects.

In any case, 1600 pounds per year is a significant contribution to my total carbon footprint—probably about 10% of the total—but not as large as the contributions from driving or food production or heating my home. For the average American, who flies only half as much as I do but uses much more gasoline and electricity, flying is actually a pretty small fraction of the total carbon footprint. And the same is true worldwide, because most people fly so much less than Americans do.

Although air travel may not currently seem like the biggest carbon concern, it will inevitably become a bigger issue in the future. Global passenger air transportation is currently growing at a rate of about 6% per year, five times as fast as the population growth rate. Further efficiency gains in air transportation will be small, and there’s currently no alternative to petroleum-based jet fuel.

The real issue with flying is that it’s so unequal. Rich people tend to fly a great deal, and increasing numbers of the middle class are becoming wealthy enough to fly 10,000 miles a year if they want to. If the world average ever gets close to that level, petroleum prices will soar and the impact on earth’s climate will be catastrophic.